England in the Middle Ages

Roman military withdrawals left England open to intrusion by agnostic, nautical champions from north-western mainland Europe, primarily the Saxons, Points, Jutes and Frisians who had long struck the banks of the Roman territory. These gatherings then, at that point, started to get comfortable expanding numbers throughout the fifth and 6th hundreds of years, at first in the eastern piece of the country. Their development was contained for certain a long time after the Britons' triumph at the Skirmish of Mount Badon, however thusly continued, overwhelming the ripe swamps of England and decreasing the region under Brittonic control to a progression of discrete territories in the more rough country toward the west toward the sixth century's end. Contemporary texts portraying this period are incredibly scant, leading to its depiction as a Dim Age. Subtleties of the Old English Saxon settlement of England are thusly dependent upon extensive conflict; the arising agreement is that it happened for an enormous scope in the south and east however was less significant toward the north and west, where Celtic dialects kept on being spoken even in regions under Old English Saxon control.

Roman-overwhelmed Christianity had, as a general rule, been supplanted in the vanquished domains by Old English Saxon agnosticism, yet was once again introduced by teachers from Rome drove by Augustine from 597. Debates between the Roman-and Celtic-overwhelmed types of Christianity finished in triumph for the Roman custom at the Chamber of Whitby (664), which was apparently about tonsures (administrative hair styles) and the date of Easter, yet more essentially, about the distinctions in Roman and Celtic types of power, religious philosophy, and practice.During the settlement time frame the grounds governed by the incomers appear to have been divided into various ancestral domains, however by the seventh hundred years, when significant proof of the circumstance again opens up, these had blended into approximately twelve realms including Northumbria, Mercia, Wessex, East Anglia, Essex, Kent and Sussex. Throughout the next hundreds of years, this course of political solidification continued. The seventh century saw a battle for authority among Northumbria and Mercia, which in the eighth century gave way to Mercian preeminence. In the mid ninth century Mercia was uprooted as the first realm by Wessex. Later in that century heightening assaults by the Danes finished in the success of the north and east of Britain, ousting the realms of Northumbria, Mercia and East Anglia. Wessex under Alfred the Incomparable was left as the main enduring English realm, and under his replacements, it consistently extended to the detriment of the realms of the Danelaw. This achieved the political unification of Britain, first refined under Æthelstan in 927 and absolutely settled after additional struggles by Eadred in 953.

A new flood of Scandinavian assaults from the late tenth century finished with the success of this unified realm by Sweyn Forkbeard in 1013 and again by his child Cnut in 1016, transforming it into the focal point of a fleeting North Ocean Domain that likewise included Denmark and Norway. Nonetheless, the local illustrious administration was reestablished with the promotion of Edward the Questioner in 1042.

Ruler Henry V at the Skirmish of Agincourt, 1415.

Ruler Henry V at the Skirmish of Agincourt, battled on Holy person Crispin's Day and closed with an English triumph against a bigger French armed force in the Hundred Years' Conflict

A disagreement regarding the progression to Edward prompted a fruitless Norwegian Intrusion in September 1066 near York in the North, and the fruitful Norman Victory in October 1066, achieved by a military drove by Duke William of Normandy attacking at Hastings late September 1066. The actual Normans began from Scandinavia and had gotten comfortable Normandy in the late ninth and mid tenth centuries.

This triumph prompted the practically complete dispossession of the English tip top and its substitution by another French-talking nobility, whose discourse meaningfully affected the English language.

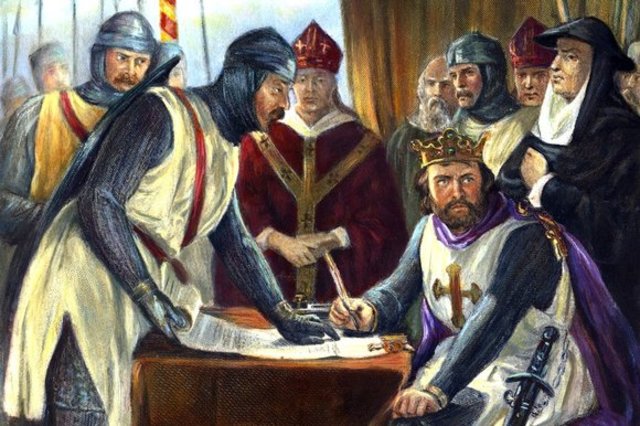

Hence, the Place of Plantagenet from Anjou acquired the English lofty position under Henry II, adding Britain to the sprouting Angevin Realm of fiefs the family had acquired in France including Aquitaine. They ruled for a considerable length of time, a few noted rulers being Richard I, Edward I, Edward III and Henry V. The period saw changes in exchange and regulation, including the marking of Magna Carta, an English legitimate sanction used to restrict the sovereign's powers by regulation and safeguard the honors of freemen. Catholic asceticism prospered, giving thinkers, and the colleges of Oxford and Cambridge were established with illustrious support. The Territory of Ribs turned into a Plantagenet fief during the thirteenth century and the Lordship of Ireland was given to the English government by the Pope. During the fourteenth 100 years, the Plantagenets and the Place of Valois professed to be real petitioners to the Place of Capet and of France; the two powers conflicted in the Hundred Years' War. The Dark Passing plague hit Britain; beginning in 1348, it at last killed up to half of Britain's inhabitants. Somewhere in the range of 1453 and 1487, a nationwide conflict known as the Conflict of the Roses pursued between the two parts of the illustrious family, the Yorkists and Lancastrians. At last it prompted the Yorkists losing the high position completely to a Welsh honorable family the Tudors, a part of the Lancastrians headed by Henry Tudor who attacked with Welsh and Breton hired fighters, acquiring triumph at the Clash of Bosworth Field where the Yorkist lord Richard III was killed.